As a result of the November 29th announcement by Prime Minister Trudeau giving conditional approval to Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Project, we have been receiving questions about what this might mean for whale species recognized to be at risk and protected under Canada’s Species at Risk Act (SARA).

We have written the following in order to answer these questions related to the potential increase in tanker traffic and whale species at risk by summarizing available information from federal documents including Recovery Strategies and Action Plans.

In addition to this review of federal documents, MERS research on Humpback Whales and the risk of vessel strike is pertinent to the potential of increased tanker traffic. Our extensive experience with Humpback Whales provides us with the knowledge of how incredibly unaware Humpbacks can be of boats and how very unpredictably they can surface. This has made our “See a Blow? Go Slow!“campaign a necessity to raise awareness about reducing the risk of collision for the sake of whale and boater safety. Our work with Humpback Whales makes us all too aware that large vessels like tankers cannot divert course fast enough to avoid hitting humpbacks.

The more vessel traffic, the greater the risk becomes.

Questions:

What are the specifics of the tankers – size, number and route?

- The Aframax tankers proposed to serve the pipeline are 245 m long and 42 m wide.

- There would be an approximate sevenfold increase in the number of tankers – from 60 to 408 tankers annually.

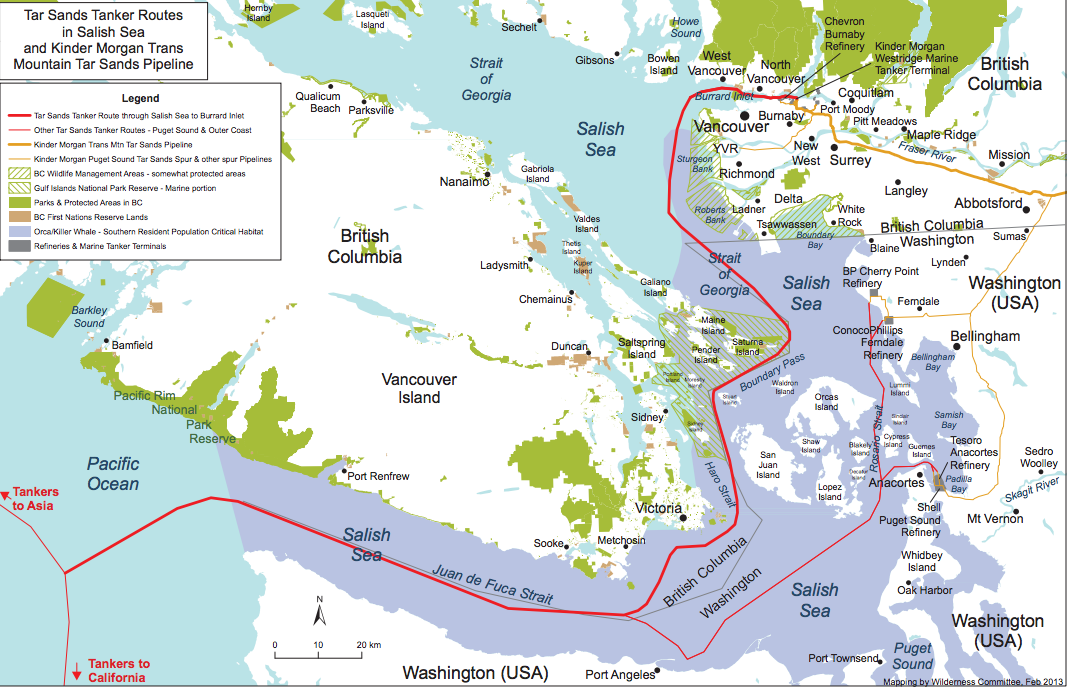

- The tankers would carry diluted bitumen to Asian and Californian refineries along the route in the figure below. Note that tanker route (red line) is shown relative to acknowledged critical habitat for the endangered southern resident killer whale population (purple area).

How important is the tanker route area to whale species at risk?

The following whale species are recognized to be at risk and are commonly present along the tanker route. They are protected under Canada’s Species at Risk Act.

- Southern Resident Killer Whales – Endangered

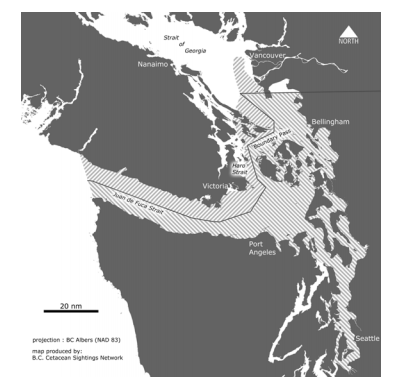

Area is designated critical habitat (see Figure 2) - Transient / Bigg’s Killer Whales – Threatened

Area is proposed critical habitat (see Figure 3) - North Pacific Humpback Whales – Threatened

In addition to the designated critical habitat (see Figure 4) there has been a recent dramatic increase in humpbacks in the Strait of Georgia and the Juan de Fuca Strait.

You will note that the area through which increased numbers of tankers would transit is designated or proposed critical habitat for all three at-risk whale species.

“Critical habitat” is defined under SARA as “the habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species that is identified as the species’ critical habitat in the recovery strategy or in an action plan for the species” (SARA s.2 (1)).”

![Figure 3: “Map showing the habitat considered necessary for meeting recovery objectives for inner coast WCT killer whales [West Coast Transient]. Area includes marine waters bounded by a distance of 3 nautical miles (5.56 km) from the nearest shore. This area includes the locations of over 90% of all individual identifications and predation events documented in BC waters during 1990-2011.” Source: Ford, J.K.B, E.H. Stredulinsky, J.R. Towers and G.M. Ellis. 2013. Information in Support of the Identification of Critical Habitat for Transient Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) off the West Coast of Canada. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2012/155. iv + 46 p. http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Csas-sccs/publications/resdocs-docrech/2012/2012_155-eng.pdf](https://mers-v1772138288.websitepro-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/screen-shot-2016-11-30-at-11-20-19-pm.png)

![Figure 4: “Locations of the four critical habitat areas [for humpback whales]: a. Southeast Moresby Island, b. Langara Island, c. Southwest Vancouver Island, d. Gil Island (DFO 2009). The existence of other areas of critical habitat for Humpback Whales in B.C. is likely.” Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2013. Recovery Strategy for the North Pacific Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa. x + 67 pp. http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/plans/rs_rb_pac_nord_hbw_1013_e.pdf](https://mers-v1772138288.websitepro-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/screen-shot-2016-11-30-at-11-10-51-pm-e1480623045844.png?w=640)

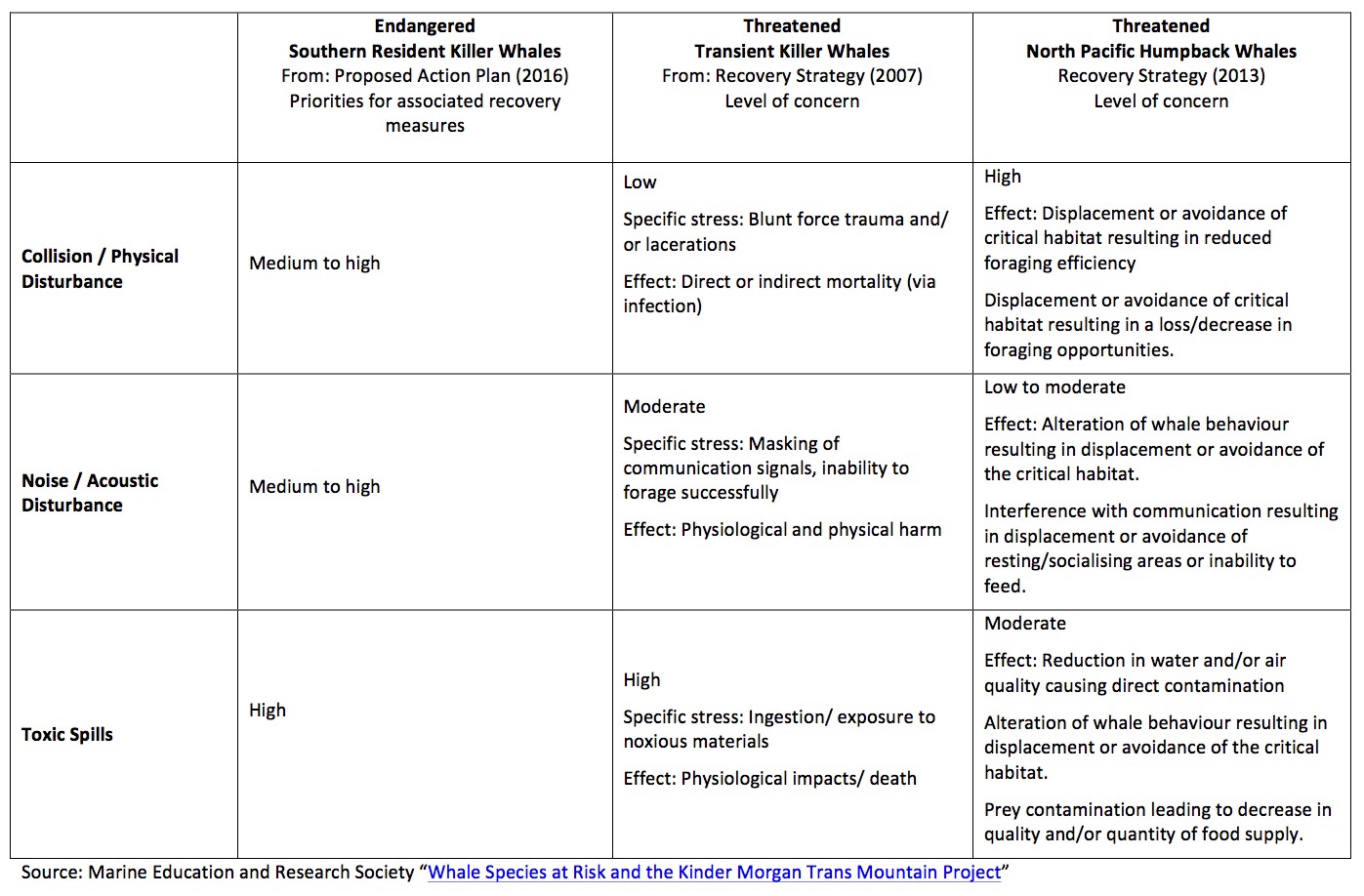

Below, we have summarized associated risks as specified in the SARA Recovery Strategies or Action Plans for whale species at risk (click to enlarge).

Further language from federal Recovery Strategies specifically referencing oil spills and/or tankers:

- Resident Killer Whale Recovery Strategy (2011): “The threat of a spill of oil or other toxic material within the areas of critical habitat pose not only an immediate and acute risk to the health of resident populations . . . but have the potential to make critical habitat areas un-inhabitable for an extended period of time. . . . While the probability of either northern or southern resident killer whales being exposed to an oil spill is low, the impact of such an event is potentially catastrophic [Note that this Recovery Strategy dates back to 2011]. Both populations are at risk of an oil spill because of the large volume of tanker traffic that travels in and out of Puget Sound and the Strait of Georgia (Baird 2001, Grant and Ross 2002) and the proposed expansion of tanker traffic in the north and central coast of BC. In 2003, 746 tankers and barges transported over 55 billion litres of oil and fuel through the Puget Sound (WDOE 2004). If the moratorium on oil and gas exploration and development is lifted in British Columbia, the extraction and transport of oil may put northern resident killer whales at additional risk.

Killer whales do not appear to avoid oil, as evidenced by the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Less than a week after the spill, resident whales from one pod were observed surfacing directly in the slick (Matkin et al. 1999). Seven whales from the pod were missing at this time, and within a year, 13 of them were dead. This rate of mortality was unprecedented, and there was strong spatial and temporal correlation between the spill and the deaths (Dahlheim and Matkin 1994, Matkin et al. 1999). The whales probably died from the inhalation of petroleum vapours (Matkin et al. 1999). Exposure to hydrocarbons can be through inhalation or ingestion, and has been reported to cause behavioural changes, inflammation of mucous membranes, lung congestion, pneumonia, liver disorders, and neurological damage (Geraci and St. Aubin 1982).”

- Transient Killer Whale Recovery Strategy (2007): “Killer whales do not appear to avoid toxic spills, as indicated by the behaviour of a group of transients in the vicinity of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 in Prince William Sound, Alaska (and described in Section 1.4.3.8). This spill was associated with unprecedented mortality of both transient and resident killer whales, which likely died from the inhalation of petroleum vapours (Matkin et al. 1999). Spills on a smaller scale have occurred in British Columbia, such as the Nestucca oil spill (875 tonnes in December 1988) in Gray’s Harbor, Washington, which drifted into Canadian waters, and the more recent spill of 50 tonnes of bunker fuel into Howe Sound from a ruptured tanker in August 2006. There is currently a considerable amount of tanker traffic in and out of Puget Sound and the Strait of Georgia, which poses a risk for killer whales (Baird 2001, Grant and Ross 2002). If the proposed 30-inch 400,000 barrel/day Gateway Pipeline is built near Kitimat, the risk of an oil spill associated with tanker traffic running from inshore waters to California and Asia will increase significantly.”

[Note the Recovery Strategy was finalized prior to the announcement rejecting the Northern Gateway Project and developments with the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain Project]. - Humpback Whale Recovery Strategy (2013): “The recent oil platform blowout in the Gulf of Mexico released an estimated 5.2 million barrels of oil (Crone and Tolstoy, 2010) is a poignant reminder of the potential for failure in engineered infrastructure in the marine environment. Even with very low odds and excellent safety records, catastrophic events can lead to undesirable outcomes. Proposed pipeline projects, associated tanker traffic, and possible offshore oil and gas exploration and development in coastal British Columbia all increase the likelihood of toxic spills in Humpback Whale habitat in the future, and underscore the importance of protecting critical habitat and supporting mitigation measures and plans.

In 1989 and 1990, following the Exxon Valdez oil spill, Humpback Whales in Prince William Sound were monitored for resulting effects. A change in abundance could not be determined, no change in calving rate was observed, and distribution varied by year, possibly related to changing prey abundance or distribution. Since there were no reports of Humpback Whales directly exposed to the spill (i.e. swimming through oil slicks), or of dead stranded whales (Dahlheim and von Ziegesar 1993), it is difficult to conclude whether Humpback Whales are vulnerable to oil spills or whether there were simply no whales in the vicinity at the time of the spill. However, other cetaceans such as Killer Whales do not appear to avoid toxic spills, and the Exxon Valdez oil spill was associated with unprecedented mortality of both Resident and Transient Killer Whales, likely resulting from inhalation of petroleum vapours (Matkin et al. 2008). Toxic spills have occurred impacting marine habitat along the B.C. coast. For example, the Nestucca oil spill (1988) resulted in 875 tonnes of oil spilled in Gray’s Harbor, Washington. Oil slicks from this spill drifted into Canadian waters, including Humpback Whale habitat. In 2006, a tanker ruptured in Howe Sound, B.C. spilling approximately 50 tonnes of bunker fuel into coastal waters. In 2007, a barge carrying vehicles and forestry equipment sank near the Robson Bight-Michael Bigg Ecological Reserve within the critical habitat for Northern Resident Killer Whales, spilling an estimated 200 litres of fuel. The barge and equipment (including a 10,000L diesel tank) were recovered without incident. When the Queen of the North sank on March 22, 2006, with 225,000 L of diesel fuel, 15,000 L of light oil, 3,200 L of hydraulic fluid, and 3,200 of stern tube oil, it did so on the tanker route to Kitimat, which is currently the subject of a pipeline and port proposal and within the current boundaries of Humpback Whale critical habitat . . .

Strong avoidance reactions to underwater noise by Grey, Humpback and Bowhead Whales has been observed at received levels of 160-170 dB re 1 µPa (Richardson et al. 1995; Frankel and Clark 2000; McCauley et al. 2000; Stone and Tasker 2006). The level of noise from a tanker may be as high as 190 dB re 1 µPa, and bathymetric features that reduce sound dissipation would further increase the level of disturbance. For this reason, fjords or channels may be particularly sensitive to noise propagation from vessel traffic. The disruption of access to these areas would limit or reduce foraging opportunities or alter behaviours that support other life processes, such as resting, socializing, and vocal interaction.

Humpback Whales exhibit strong site fidelity for feeding along the B.C. coast (DFO 2009; Ford et al. 2009) and increased acoustic disturbance in these areas may be detrimental to the quality and accessibility of the feeding grounds.”

What mitigation measures has the federal government put forward?

On November 7th, the federal government announced the “Ocean Protection Plan” for which “Canada will invest $1.5 billion over five years in long-needed coastal protections, with an action plan to deliver results for the coming decade. This Plan will engage communities, first responders, and governing authorities to work together effectively to respond to emergencies.” Many details have not yet been released.

The announcement includes the following plans to address specific risks:

Collision: “The Government of Canada will . . .. Work with partners to implement a real-time whale detection system in specific areas of the species’ habitat to alert mariners to the presence of whales, which will allow them to better avoid interactions with this and other marine mammal species.”

Noise: “The Government of Canada will . . . Take action to better understand and address the cumulative effects of shipping on marine mammals, such as the southern resident killer whales pods . . . This includes work to better establish baselines for noise and consideration of options to mitigate these effects.”

Oil spills: “The Government of Canada will fund improved research capacity to seek safe, reliable, and more effective technologies to clean up oil spills. Research into new clean-up technologies is an essential part of a world-leading marine safety plan.

New investments will fund research to help improve emergency response to marine pollution incidents on the water drawing on the expertise and experience of the science community both in Canada and abroad.

New international partnerships will give Canadians access to the best technology available for spill clean-up. A program will build on the work of Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s world-leading Centre for Offshore Oil, Gas and Energy Research and will encourage collaboration on scientific research with Indigenous and local communities, international research facilities and industry.”

Federal documents that have informed the above:

- Canada’s Oceans Protection Plan

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2007. Recovery Strategy for the Transient Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Vancouver, vi + 46 pp

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2011. Recovery Strategy for the Northern and Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series, Fisheries & Oceans Canada, Ottawa, ix + 80 pp.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2013. Recovery Strategy for the North Pacific Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa. x + 67 pp.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2016. Action Plan for the Northern and Southern Resident Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Action Plan Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa. iii + 32 pp.

- Ford, J.K.B, E.H. Stredulinsky, J.R. Towers and G.M. Ellis. 2013. Information in Support of the Identification of Critical Habitat for Transient Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) off the West Coast of Canada. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2012/155. iv + 46 p.