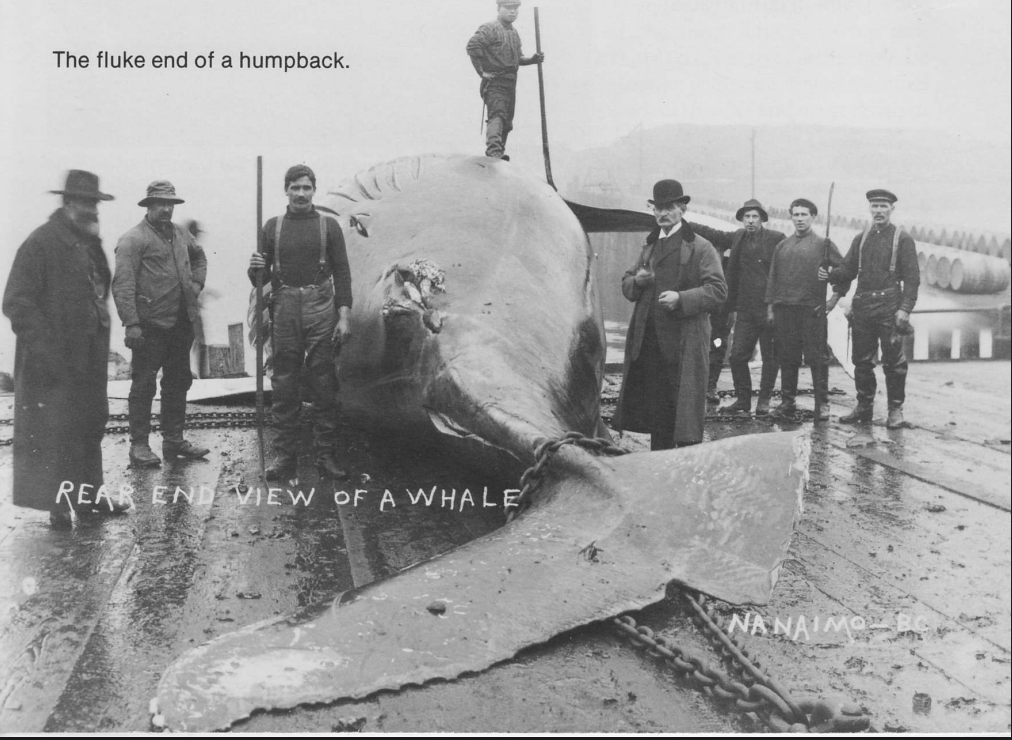

In the summer of 2012, a young humpback whale stranded near Vancouver, British Columbia. The whale was entangled in offshore longline gear; gear that had become almost unrecognizable to experts because the whale had been entangled for so long that the hooks in the gear had rotted away. Soon after washing up on the beach, the whale passed away. This young humpback is an example of how these dangerous entanglement events can go unseen or unreported for long periods of time.

(photo: Caitlin Birdsall, Cetacean Sightings Network)

Entanglement in fishing gear has been identified by the governments of Canada and the United States as one of the major threats to humpback whales. The most immediate concern when a whale becomes entangled is that it will drown; whales can become so severely tangled up in the fishing gear that they cannot make it to the surface to breathe. Humpbacks and other large whales, however, often swim away from the site of entanglement, dragging some fishing gear with them. This fishing gear can lead to serious injuries and infections, and can make it impossible for whales to travel and feed effectively.

If whales like the one in Vancouver can be entangled for months (or more) without being seen and reported, how can we get an accurate estimate of how often humpback whale entanglement occurs? Researchers from the Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies have noted that entanglements tend to leave characteristic scars and injuries on a part of a humpback’s body known as the caudal peduncle, or tailstock. This is basically where a humpback’s tail meets the rest of its body. By systematically photographing humpback whales’ tailstocks as they dive, and later examining these photographs to look for entanglement-related scarring or injuries, we can get an estimate of what proportion of whales in B.C. have survived a previous entanglement event.

(photo: Jared Towers, MERS)

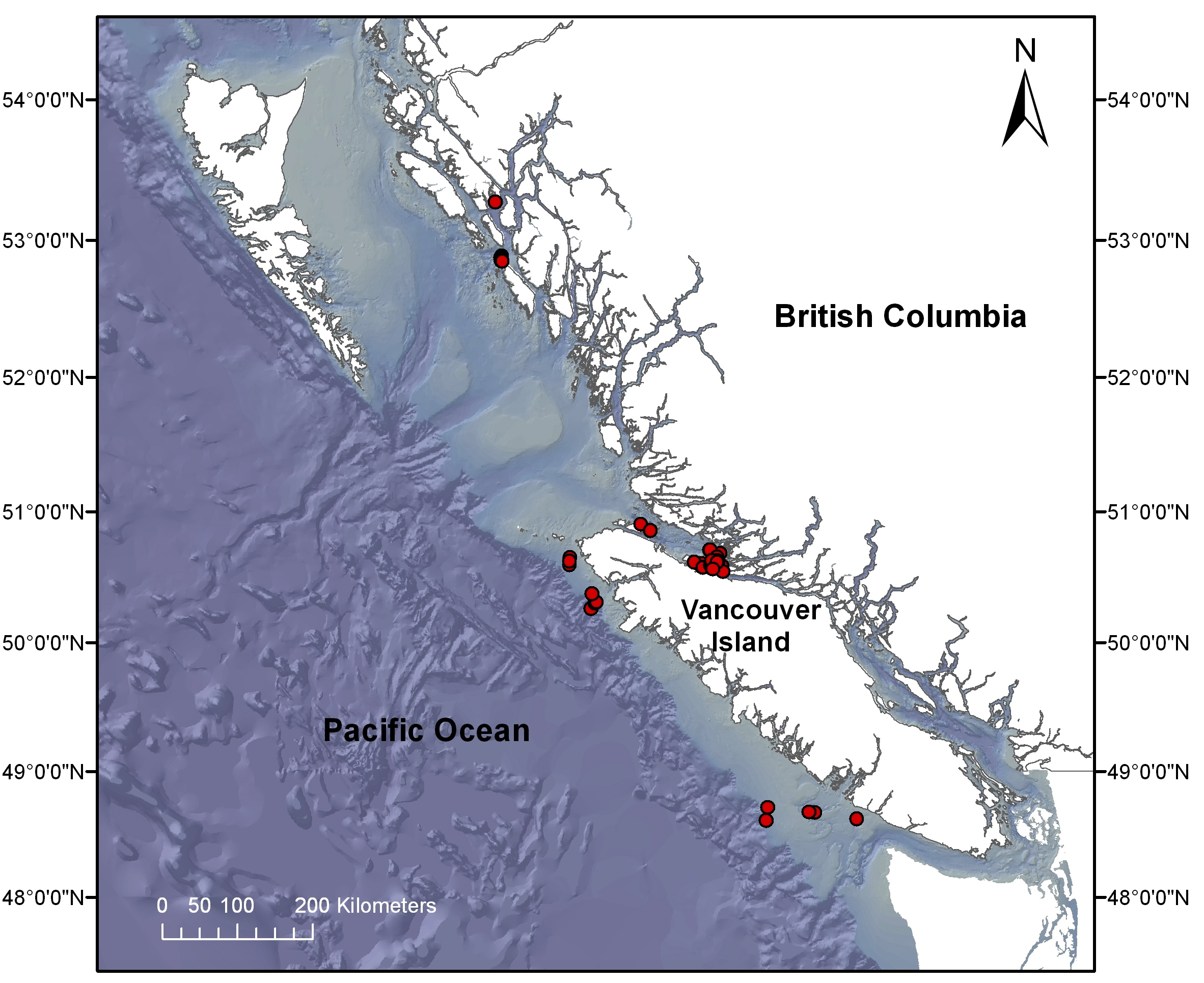

Since 2010, MERS researchers have been collecting the required photographs and data to estimate how frequently humpback whales off the coast of B.C. are becoming entangled in fishing gear. During the first three years of the study, we focused most of our research effort around Vancouver Island and the central coast of B.C. (see map below). However, there are still many areas of the coast from which we have not been able to collect these data. In order to obtain an accurate estimate of how frequently humpback whales are becoming entangled in fishing gear, we are hoping to acquire enough donations to expand our study to include more of the coast in upcoming field seasons.

An accurate estimate of how often humpback whales are becoming entangled in fishing gear is imperative for understanding the threats to these whales in the North Pacific, which are currently listed as threatened under Canada’s Species at Risk Act and as endangered under the United States’ Endangered Species Act.

(photo: Christie McMillan, MERS)

To donate to MERS’ entanglement research, click here. See our website for more information about MERS humpback whale research and about the threat of entanglement for humpback whales, or feel free to e-mail us at mersociety@gmail.com with any questions.

MERS would like to thank everyone who has contributed to and supported this study thus far, especially Mountain Equipment Co-op, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the whale watchers, researchers, and community members of Northern Vancouver Island.

~ Christie, Jared, and the rest of the MERS team

References:

Fisheries and Oceans Canada. (2010). Recovery Strategy for the North Pacific Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Canada [DRAFT]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa. 51 pp.

Robbins, J. and Mattila, D.K. (2001). Monitoring entanglements of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the Gulf of Maine on the basis of caudal peduncle scarring. Report to the International Whaling Commission. Document SC/53/NAH25.