By Jackie Hildering

MERS Education & Communications Director.

Do terrestrial predators like wolves and bears feed on marine mammals?

Why yes they do. They not only scavenge on the energy rich carcasses of dead marine mammals when they wash ashore but, there are cases of terrestrial predators hunting marine mammals!

Scavenging:

Imagine the calories and further nutrition available from a dead marine mammal. When whales die and sink to the depths, they are referenced as “whale fall” and feed communities of organisms for decades.

What would be a good term for when a dead marine mammal washes ashore and delivers a bounty of nutrients . . . an “all-you-can-eat-buffet”? Why, with the smell that exudes from a decaying marine mammal, there’s even the equivalent of a dinner bell. Or, in considering how many calories are made available so easily, maybe a better label would be “a free lunch”?

I’ll never forget watching black bears lunching on a dead whale, their noses white from the whale’s blubber, reminiscent of how a child’s face gets covered when enthusiastically eating ice cream. I regret that I did not have a camera with me that day.

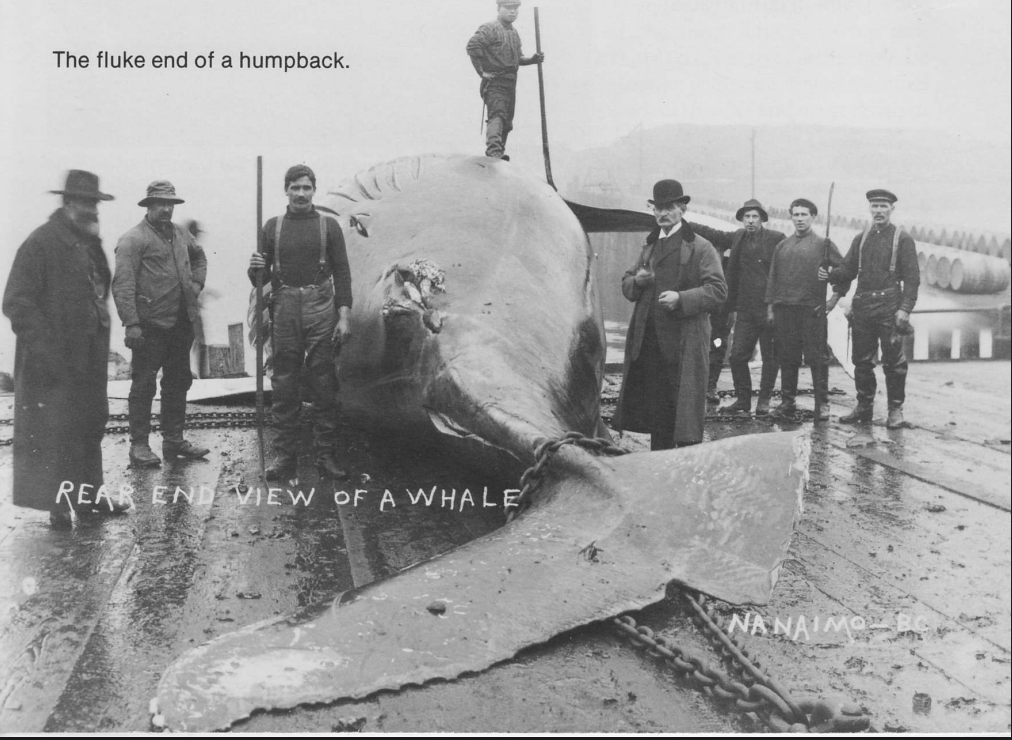

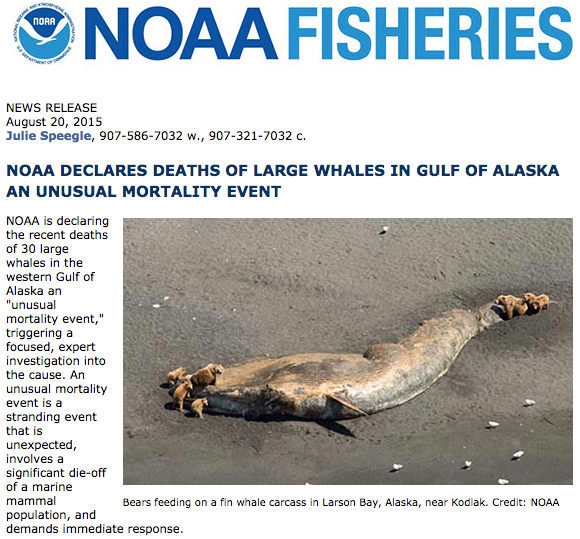

Very thankfully, others have generously shared their images to make this blog possible. No words can have the same impact as the following images in communicating examples of how terrestrial predators feed on marine mammals; and, how nutrients do not go wasted in nature.

The above photo may already be familiar to you. It has been widely used in news stories related to the “Unusual Mortality Event” of humpback and fin whales in 2015. Taken by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, it shows seven brown bears (aka grizzly bears) feeding on a dead fin whale. (Please see the end of the blog for the hypothesis of what may have caused the death of the whales).

Alaskan wildlife photographer Brad Josephs reports observing twelve brown bears and several coastal wolves in the area of another dead fin whale in Alaska in 2015.

Studies on the interactions of wolves and bears when feeding on a dead whale include the work of Tania M. Lewis and Diana J.R. Lafferty using remote cameras around a dead humpback whale in Glacier Bay, Alaska in 2010. In their research, they found little evidence of interspecies aggression between the wolves and bears in the four month long “Blubber Bonanza” provided by the humpback whale carcass. There are, however, likely to be dominance displays between brown bears.

Ivan Dubinsky recently documented coastal wolves in British Columbia scavenging on what appears to be a Pacific white-sided dolphin carcass.

April Bencze’s photos from the Central Coast of BC provide an example of coastal wolves scavenging on a dead Steller sea lion.

And here you have Black Bears feeding on a sea lion carcass, photo by Erica Beauchamp.

The remains found in wolf scat by Stacey Hrushowy, reveal that the wolf ate a Pacific harbour seal. Was this the result of scavenging or . . . predation?!

Predation:

Cougar scat has also been found to contain remains of Pacific harbour seals and California seal lions. But, no matter how stealthy, wily and fleet-footed the predator, it is impossible to conclude from a scat sample alone if marine mammals were predated upon or scavenged. Observations are needed.

Wolves have been observed hunting seals, California sea lions and even a juvenile Steller sea lion on our coast. Notably, there is one wolf on a small, rocky island that has been repeatedly documented making a living by eating Pacific harbour seals hauled out on the rocks. I will not share further details of the location for fear of the wolf being disturbed (or worse) and am grateful that others who are aware of the location have the same sensitivity and concern.

And, THEN, there’s the case of coastal wolves possibly predating on sea otters! This is being studied by Dr. Chris Neufeld of Quest University who has shared his research in presentations entitled: “Life and Death on a Small Island: Novel Interactions Between Wolves, Sea Otters, and People in Kyuquot Sound, BC“.

The hypothesis is that this is predation rather than scavenging; that the wolves ambush the otters when they briefly are on land. It is anticipated that documentation, including Dr. Neufield’s use of trail cameras, will soon lead to conclusions about whether this is truly predation and, if it is, what strategies this wolf pack has learned whereby the succeed in hunting sea otters.

See below for Meredith Lewis’ remarkable photos of the wolves feeding on sea otters.

An unfortunate but necessary footnote:

With regard to the Unusual Mortality Event of humpback and fin whales referenced above, a hypothesis about how they died is that warmer waters led to increased algae growth, including species like red tide that produce biotoxins (in the case of red tide, it is the neurotoxin domoic acid and there is also saxitoxin produced by another harmful algae bloom). These biotoxins bioaccumulate up the food chain, impacting top level predators like the whales. More information about the hypothesis at this link.

Whales too can have high loads of human created persistent bioaccumulative and toxic chemicals like PCBs, DDTs and PBDEs (brominated fire retardants).

Thereby, if marine mammals have toxins in their systems, terrestrial predators feeding on them could further bioaccumulate the chemicals. This is certainly the case with the bioaccumulative toxins of human origin. In the case of demoic acid from red tide algae, it appears that this chemical dissipates quickly from the body whereby terrestrial predators would not be at risk of further bioaccumulation through scavenging on marine mammal remains. This is why it has been so difficult to confirm if indeed harmful levels of demoic acid are responsible for the whale deaths; the chemical quickly dissipates from the dead whales’ bodies. (With thanks to Dr. Andrew Trities for this information).

Resources: