Last updated: January 28, 2026

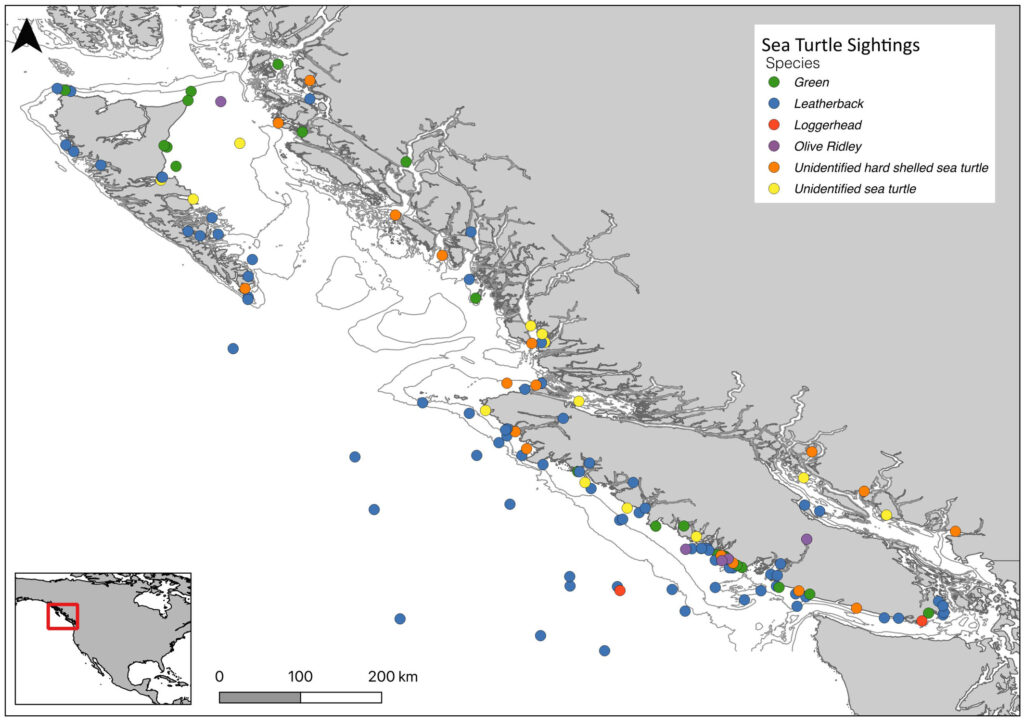

Information added from Spaven et al., 2026 “They’re Out There, You Know: Sea Turtle Sightings and Strandings in Canadian Pacific Waters”

Yes, there are Leatherback Turtles off British Columbia’s coast!

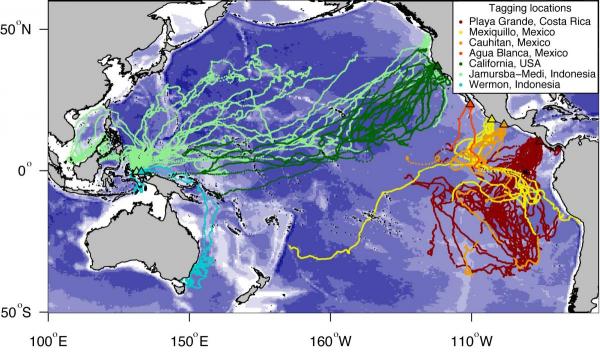

In fact, the cold ocean off BC is extremely important to this endangered sea turtle species and they are protected as an endangered species under Canada’s Species at Risk Act. Leatherbacks migrate all the way from Indonesian to feed on the jellyfish here.

See our two-minute animation below about the presence of these endangered awe-inspiring giants and how we can all help their survival.

Please help raise awareness:

- Amazing Facts – click here.

- Threats and What You Can Do – click here.

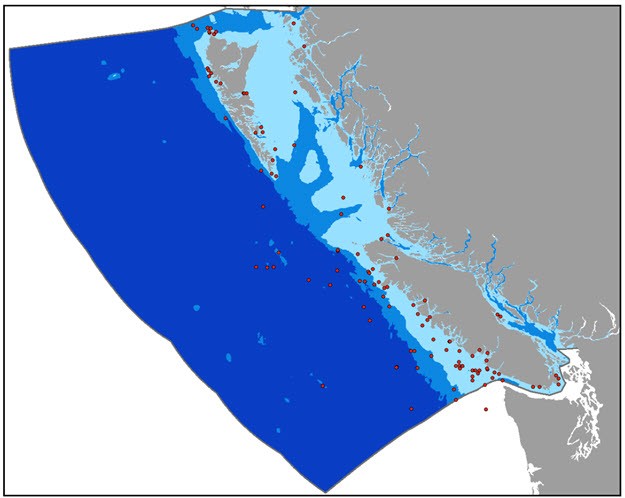

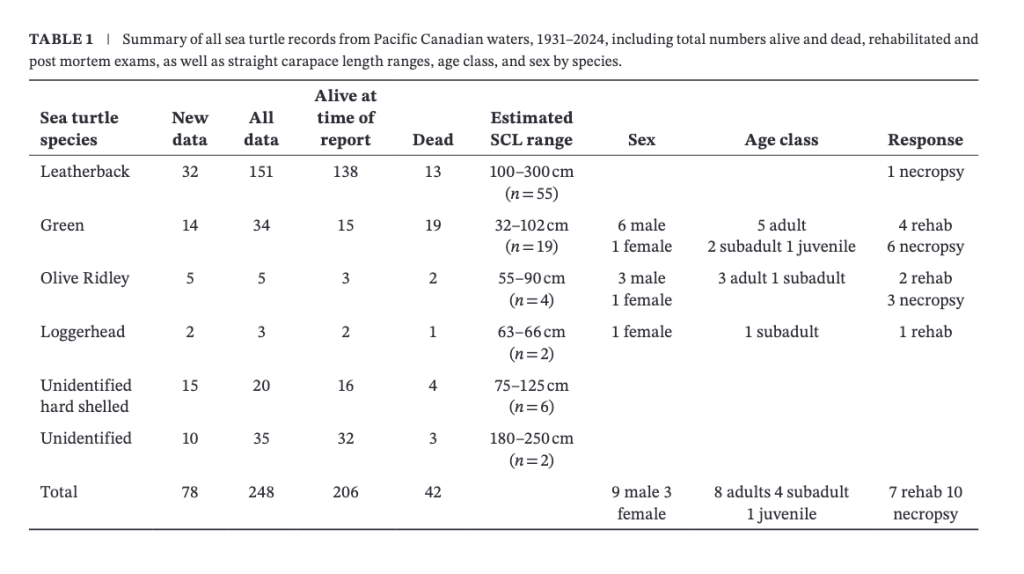

- Number of Sightings (only 151 Leatherbacks sighted in BC waters since 1931) – click here for details.

- Resources – click here.

Giants off BC’s Coast

There are Leatherback Turtles in almost every ocean of the world, and all are at risk. Only about 5% of the Pacific population is left. Even though so few of us know of their existence, there have been 152 Leatherbacks documented off the coast of BC since 1931 (Source: 151 up to 2024 from Spaven et al., 2026 + a July 2025 sighting referenced below). 91% were alive when sighted.

Very likely, there have been more, but their presence is often undetected or unreported. Raising awareness of #leatherbacksinbc is very valuable to the research being done to reduce threats to Leatherbacks. Please report sightings off the coast of BC to 1-866-I-SAW-ONE and see below for further positive actions. Click here for where to report sightings of Leatherbacks of Canada’s Atlantic coast.

Threats and Solutions

Leatherback Turtles spend the vast majority of their lives at sea. Off British Columbia’s coast, threats to the survival of these endangered giants include entanglement in fishing gear and debris; collision with boats; contamination; and . . . plastic pollution.

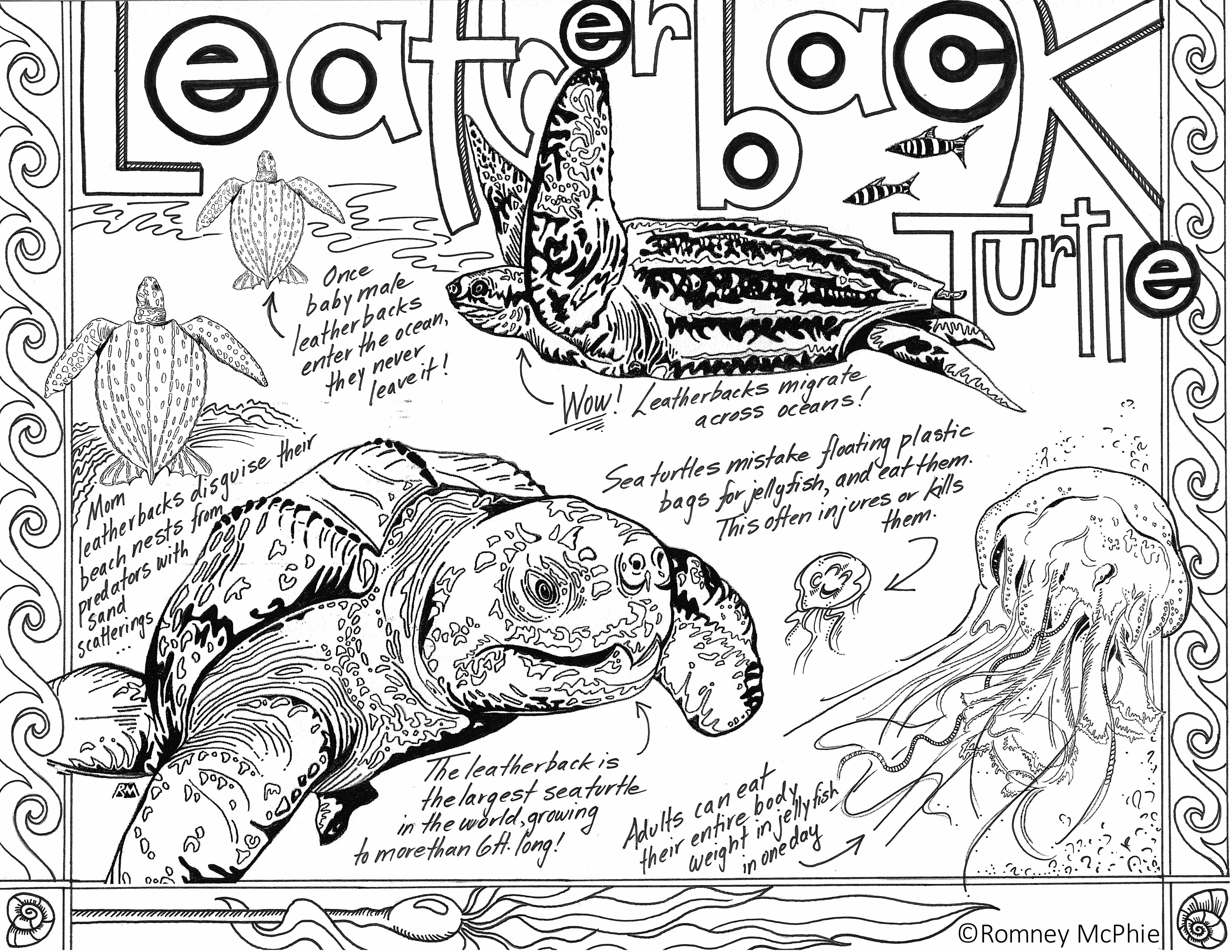

In a global study of 408 dead Leatherback Turtles, more than 30% had plastics in their intestines (Mrosovsky et al, 2009). Sea turtles accidentally eat plastics because they cannot discern them from their jellyfish prey. The ingested plastics can cause death due to internal injury and/or by blocking the intestines which can cause malnutrition or starvation. Ingested plastics also increase buoyancy which further decreases Leatherbacks’ chances of reproduction and survival.

The impacts of climate change are also a concern to Leatherback survival due to impacts on prey availability, beach erosion, toxic algae blooms, and nest temperature.

The loss of these top-level predators can have far-reaching impacts on marine ecosystems.

Screen grab from animation above. ©MERS.

Video below by the Canadian Sea Turtle Network, makes clear how easy it can be for a Leatherback to mistake plastic for their jellyfish prey.

What YOU can do!

- Reduce your use of plastics, especially plastic bags.

- NEVER release balloons into the air.

- Help increase knowledge of #leatherbacksinbc, and the threats they face. Take our free, online Whale-Safe Boating course, which includes information about Leatherbacks and reducing threats to marine megafauna.

- Report sightings to the Ocean Wise Sightings Network at 1-866-I-SAW-ONE or use the Ocean Wise WhaleReport app. The app has the byproduct of alerting verified, large vessel traffic to avoid risk of collision and noise impacts through the Whale Report Alert System (WRAS).

- Remove litter / marine debris e.g. the Great Canadian Shoreline Clean-Up.

- Know if your seafood is sustainable through the Ocean Wise Seafood Program.

- Reduce the impacts of climate change by reducing your carbon footprint.

In other parts of the world, additional threats include egg and turtle poaching and habitat loss for nesting due to beach development and erosion. In the United States and other parts of the world, Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) are being used on shrimp trawler nets to reduce the number of sea turtles that die due to entanglement / bycatch.

Amazing Leatherback Facts

- They have survived since the time of dinosaurs, for more than 100 million years.

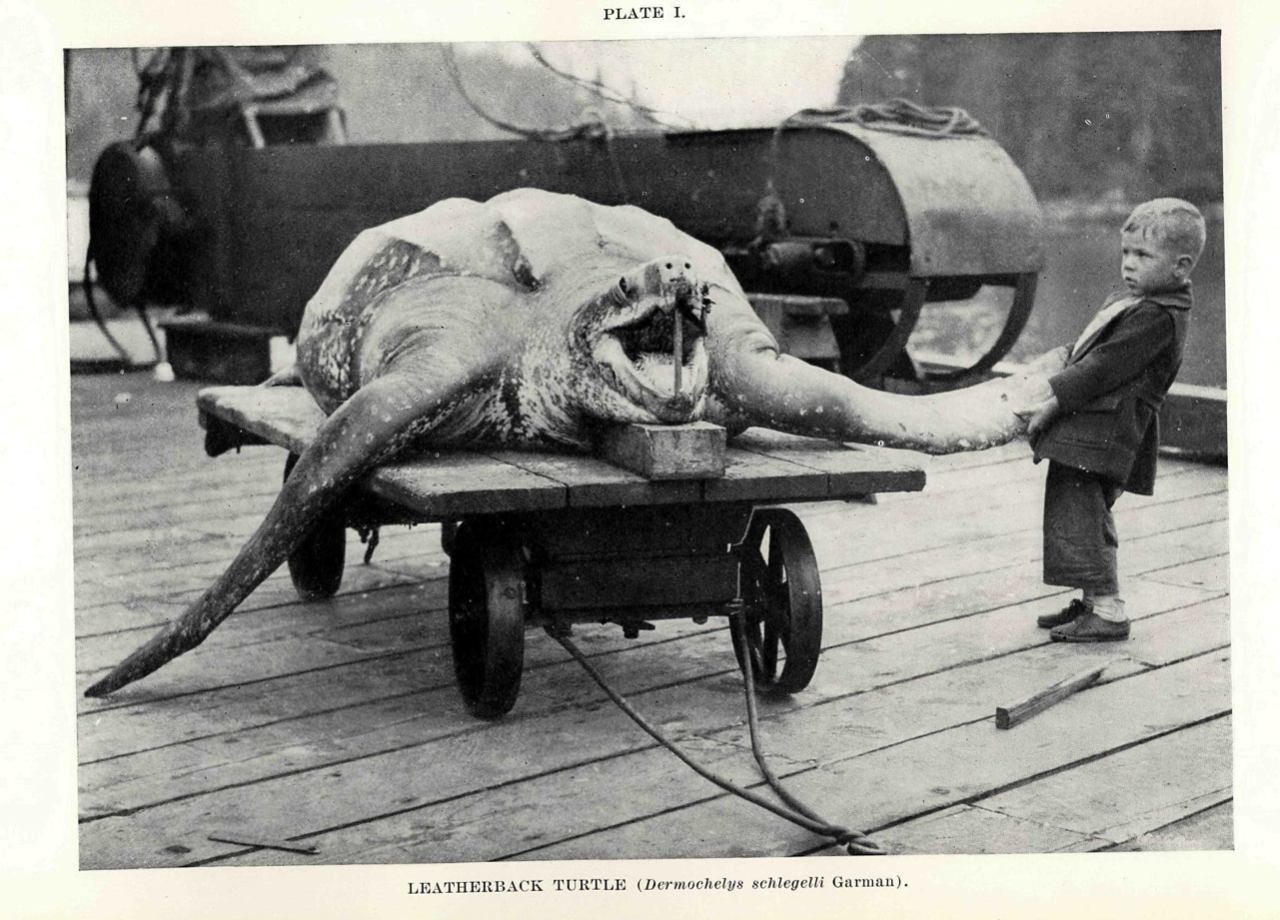

- Leatherbacks are one of the biggest reptiles in the world and likely the fastest growing. In the Pacific they are up to 2 m long and over 650 kg. That’s about the size of a Smart Car! Males and females are about the same size but, in males, the tail is longer, usually extending beyond the rear flippers. (Leatherbacks in the Atlantic are bigger on average, with the largest recorded mass being 915 kg.)

- They are known to dive to depths of 1,270 m and can stay underwater for up to 85 minutes before surfacing to breathe (dives are more often ~30 minutes).

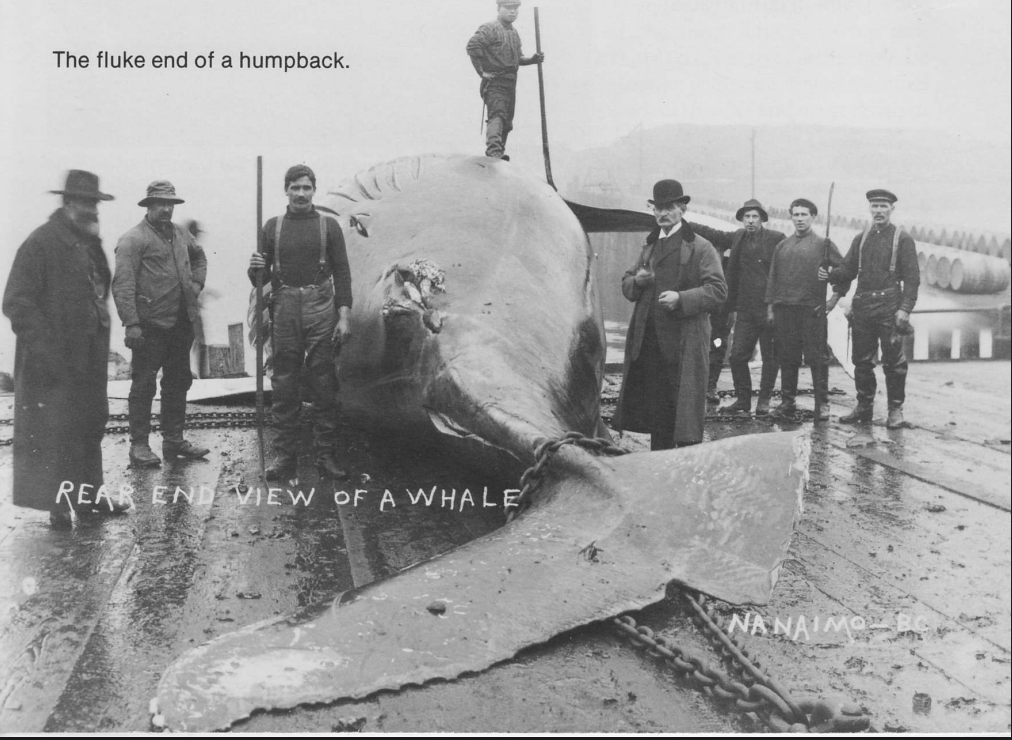

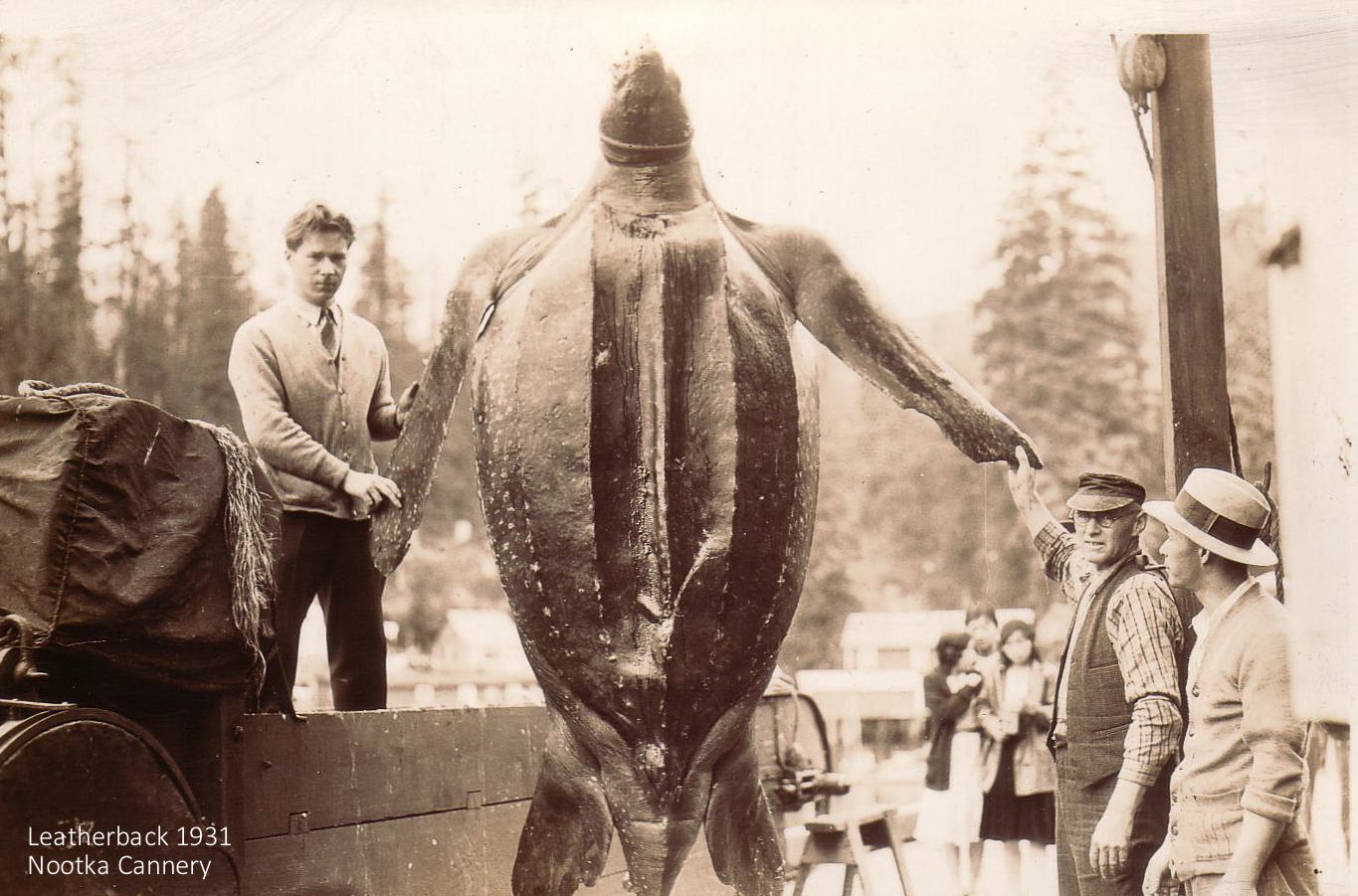

Source: Nicholson, G. 1963. Vancouver Island’s West Coast 1762-1962.

- Leatherbacks are the only sea turtle species that doesn’t have a hard shell. As their name suggests, their backs are covered with rubbery, leather-like skin. It is blue-black and this soft pad covers small bones (osteoderms) that fit together like a puzzle, making the shell (carapace) flexible and able to compress when Leatherbacks go for deep dives.

- They are also the only sea turtle that does not have scales on their head or flippers.

- Every Leatherback Turtle has unique pink markings on the top of their heads. It is believed that this patch (the “pineal spot”) may allow Leatherbacks to sense light and/or navigate. Because they are distinct, these markings help scientists identify Leatherbacks as individuals.

- Leatherbacks are unlike any other living reptile because they have a thick layer of fat that allows them to deal with cold water. Leatherback Turtles are “gigantotherms” – they can stay warm when in cold waters like those off BC, while not overheating in the warm waters like those in Indonesia due to the combination of having fat for insulation; being able to change blood flow to release or conserve heat; varying their swimming speed; and having a large body mass. They do not go into “cold shock” like other sea turtle species, maintaining a body temperature of ~25°C despite encountering temperatures from 0.4 to 15°C. The biggest Leatherbacks are more likely to be the ones seen off Canada’s Pacific coast because the larger individuals are better able to retain body heat.

- They spend their lives at sea. Leatherback Turtles mate at sea and males never return to shore after they hatch. Only females go to shore every 2 to 3 years to lay eggs, returning to the nesting beaches where they were born.

- No one knows how they navigate over such long distances. Despite ocean currents, they find their way to and from their natal nesting beaches to cold jellyfish rich waters.

- Leatherbacks are the fastest sea turtle species. They can swim up to 95 km/day at speeds of up to 9.3 km/hour (average ~38 km/day and ~2.5 km/hour). In addition to their long, powerful front flippers, it is believed that the their tear-drop shaped carapace with its 7 distinct ridges makes them such fast swimming turtles.

- They can’t swim backwards which contributes to the risk of getting entangled in fishing gear and is why they cannot be in aquariums. They injure themselves by swimming forward against the sides of the tank and can develop lethal fungal infections are a result.

- Lifecycle – so little is known! Estimates for the age of sexual maturity vary from 2 to 14 years. If females succeed in making the great migration back to the beaches where they were born, they dig a hole with their rear flippers (most often at night), lay about 100 eggs, compact the nest and return to sea (takes 80 to 120 minutes in total). Each clutch also contains around 50 yolkless eggs. The purpose of these infertile eggs is unknown. Females lay 4 to 6 clutches per season, at 8 to 12 day intervals. The babies hatch after 60 to 65 days and go straight to sea. They stay in warm waters until they have a carapace length of about 100 cm. In addition to the many human-created threats, the eggs and hatchlings face the risk of nest disturbance and predation by animals such as rats, birds, snakes, crabs, dogs, cats and pigs. Also unknown are the life expectancy of Leatherbacks and how long they can reproduce.

- Nest temperature is a concern. Temperature determines the sex of the hatchlings. When the temperature is between 29.25 to 29.5°C, equal number of males and females hatch. If the nest temperature is lower, the hatchlings are male and if the temperature is higher, the hatchlings are female. Climate change related concerns include that warmer nests would lead to fewer males being born and, also that the hatchlings could die because of high nest temperatures.

- Leatherback Turtles may have the largest distribution of any vertebrate on Earth. In addition to being in the Pacific Ocean, there are populations of Leatherbacks in the Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. All are at risk.

Known Leatherback Turtle sightings off BC’s coast since 1931

- 152 Leatherbacks since 1931 (151 up to 2024 from Spaven et al., 2026 + July 2025 sighting referenced below). 91% were alive when sighted.

- Latest known sighting – July 14, 2025 near Langara Island, Haida Gwaii by Victoria Bradshaw and Aidan Horne. See video below.

Resources

-

- Bailey, H., Benson, S. R., Shillinger, G. L., Bograd, S. J., Dutton, P. H., Eckert, S. A., Morreale, S. J., Paladino, F. V., Eguchi, T., Foley, D. G., Block, B. A., Piedra, R., Hitipeuw, C., Tapilatu, R. F. and Spotila, J. R. 2012. Identification of distinct movement patterns in Pacific leatherback turtle populations influenced by ocean conditions. Ecological Applications, 22: 735–747. doi:10.1890/11-0633

- BC Cetacean Sightings Network. Leatherback Sea Turtle.

- Bostrom BL, Jones TT, Hastings M, Jones DR. 2010. Behaviour and Physiology: The Thermal Strategy of Leatherback Turtles. PLoS ONE 5(11): e13925.

- Canadian Wildlife Federation; Leatherback Sea Turtle 101.

- CBC News; August 25, 2018; Rare sighting of leatherback off B.C. coast raises issue of plastic pollution

- COSEWIC. 2022. COSEWIC status appraisal summary on the Leatherback Sea Turtle Dermochelys coriacea, Pacific population,in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xxvii pp. (Species at Risk Public Registry).

- Davenport, J., Fraher, J., Fitzgerald, E., McLaughlin, P., Doyle, T., Harman, L. & Cuffe, T. (2009) Fat Head: An analysis of head and neck insulation in the leatherback turtle, Dermochelys coriacea. Journal of Experimental Biology: 212,2753-2759.

- DFO. 2014. Advice relevant to the identification of critical habitat for Leatherback Sea Turtles (Pacific Population). DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Sci. Advis. Rep. 2013/075.

- DFO. Underwater World – Leatherback Turtle.

- DFO. Unpublished data.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2019. Action Plan for the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Action Plan Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa. iii + 23 pp.

- Fritts, T. 1982. Plastic bags in the intestinal tract of leatherback marine turtles. Herpetological Review 13(3): 72-73.

- Helms, Sarah E, Duncan, Emily M., Broderick, Annette C., Galloway, Tamara S., Godfrey, Matthew H., Hamann, Mark, Lindeque, Penelope K., and Godley, Brendan J. Plastic and marine turtles: a review and call for research. 2015. ICES J. Mar.Sci. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsv165.

- Inside Nature’s Giants: The Leatherback Turtle (45 min video).

- Jones TT, Bostrom BL, Hastings MD, Van Houtan KS, Pauly D, Jones DR. 2012. Resource Requirements of the Pacific Leatherback Turtle Population. PLoS ONE 7(10): e45447. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045447.

- Leatherback Trust. Whey Leatherbacks and Sea Turtles Matter.

- Mrosovsky, N., Geraldine D. Ryan, and Michael C. James. 2009. Leatherback Turtles: The Menace Of Plastic. Marine Pollution Bulletin 58.2: 287-289.

- Pacific Leatherback Turtle Recovery Team. 2006. Recovery Strategy for Leatherback Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) in Pacific Canadian Waters. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Vancouver, v + 41 pp.

- Sato, C. L. 2016. Periodic status review for the Leatherback Sea Turtle in Washington. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Olympia, Washington. 17+iii pp.

- Schuyler Qamar A., Wilcox Chris, Townsend Kathy A., et al (2015) Risk analysis reveals global hotspots for marine debris ingestion by sea turtles. Global Change Biology 22:567–576. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13078

- Spaven, L.D., Migneault, A., Dracott, K., Birdsall, C. Danelesko, T., Raverty, S., Ford, J.K.B. 2026. They’re Out There, You Know: Sea Turtle Sightings and Strandings in Canadian Pacific Waters. Ecology and Evolution.

- Spaven, L.D., Ford, J.K.B, and Sbrocchi, C. 2009. Occurrence of leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) off the Pacific coast of Canada, 1931-2009. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2858: vi + 32 p.

- Species Survival Commission -International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2009. Leatherback Turtles and Climate Change.

- Wilcox, C., Puckridge, M., Schuyler, Q. A., Townsend, K. and Hardesty, B. D. (2018) A quantitative analysis linking sea turtle mortality and plastic debris ingestion. Scientific Reports, 8 (12536).