Yes, you read the title right. We’re sharing an account that gives insight into food web dynamics, adaptations, and really bad luck.

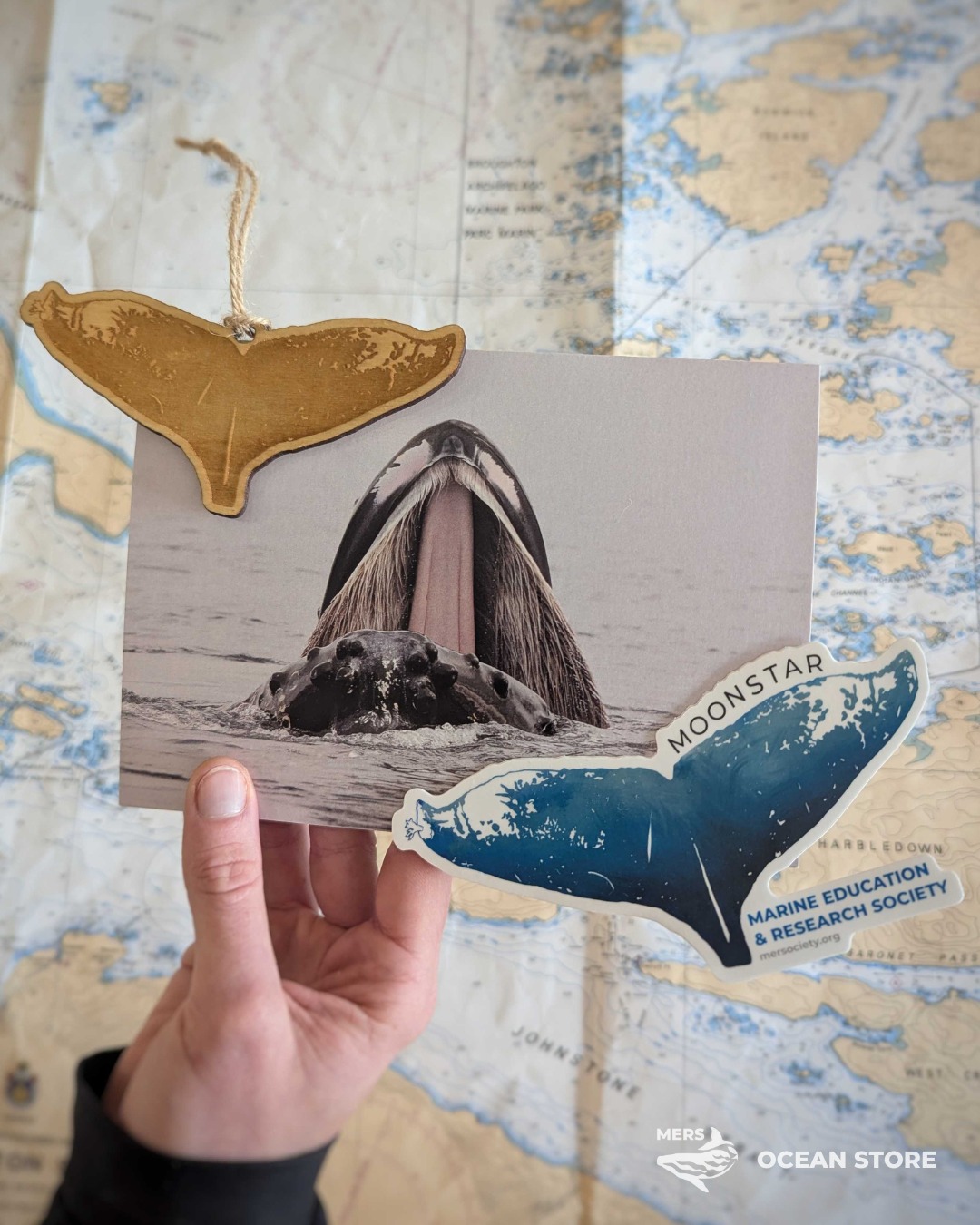

On September 11th, 2025, we were identifying individual Humpback Whales while working with a conservation film crew.

We had just documented Humpback Whale Ripple (BCX1063) when videographer Jack quietly said, “She just spat out some fish.”

What? She spat OUT fish?!

Tavish quickly got the drone over the scene, and we brought the boat over. He counted 21 rockfish at the surface. Upon collecting one, we could determine they were Widow Rockfish (Sebastes entomelas) and that they all appeared to have signs of barotrauma.

Barotrauma? Many rockfish species are particularly sensitive to reductions in pressure due to the expansion of air in their swim bladders. The swim bladder is a buoyancy-control organ and, even when slowly brought from a depth of 20 m (60’), a rockfish’s swim bladder can expand so much that it pushes the fish’s eyes out of their sockets and their esophagus out of their mouth. This prevents them from getting back below the surface on their own.

Barotrauma is reversible if the fish can quickly be brought back down to greater depth. We did not get the chance. Read on.

What likely happened is that Ripple engulfed the Widow Rockfish while feeding at depth, as a by-product of targeting a school of juvenile Pacific Herring. Humpbacks are not known to feed on rockfish, and Ripple clearly was giving two fins down to them being in her mouth.

The spines of the Widow Rockfish were either uncomfortable in her mouth and/or the fish were too big to fit down her narrow throat, so… out they had to go.

An interesting variable to consider is that this fall, there was another intrusion of Short-tailed Shearwaters (Ardenna tenuirostris) around northeast Vancouver Island similar to 2021. That is the only other time we know of thousands of this species being in the area.

Shearwaters have a very different effect on Humpback feeding than diving birds like Common Murres. When Common Murres feed on juvenile Herring, they collectively cause the fish to be “held” near the surface by targeting them from below. This makes for a “ball” of fish near the surface that Humpbacks will often benefit from. They can get a dense concentration of fish (with no benefit to the birds).

But the Shearwaters “bomb” the fish from above and, unless there are a whole lot of Common Murres below the fish, this will cause the school of fish to split. So, not surprisingly, we observe far less feeding near the surface by Humpbacks when there are a lot of Shearwaters and not enough Murres to counterbalance them.

In the flurry of this activity, the Shearwaters were picking at the Widow Rockfish. And then, seemingly out of nowhere, a Bald Eagle swooped down, grabbed one of the Widow Rockfish in their talons, and flew off to their nest.

And so, there is the fish who flew.

Minutes before, this fish would have been swimming midwater, their swim bladder holding the correct amount of air for that depth. Then, along came Ripple – still needing to bulk up before her migration to the warm-water breeding grounds – with the Shearwaters likely decreasing the energy efficiency of how she could feed.

She engulfed the fish. She swam upward. The fishes’ swim bladders expanded due to the reduced pressure. Then there was light, when Ripple opened her mouth and released the fish at the surface. But there could be no swimming away. The fish were trapped and easy prey because of barotrauma.

This is the first time we have ever documented any rockfish species being “spat” out by a Humpback, let alone with certainty about which Humpback had engulfed them.

We share this account for what it offers in understanding just how connected the strands of the food web are – birds, fish, whales – let alone all the other environmental variables impacting the number and distribution of species.

Also, if you are having a bad day, think of the fish that flew and how things could be much worse. The fragility, unpredictability, and sometimes absurdity of life are things that many of our two-legged species can relate to.

Humans involved in documenting this:

MERS team members – Jackie Hildering and Callyn Holder.

Film crew – Jack Gawthorp and Tavish Campbell.

Sources:

Rockfish Barotrauma and how it can be reversed – blog by MERS team member, Jackie Hildering.