By Jackie Hildering & Christie McMillan,

Humpback Researchers, Marine Education & Research Society

Update May 2024: Where to watch Planet Earth III.

Also see our article featured on the BBC’s “Making Planet Earth III” page.

Background on our role filming Humpback Whales with the BBC for Planet Earth III. – Episode 7.

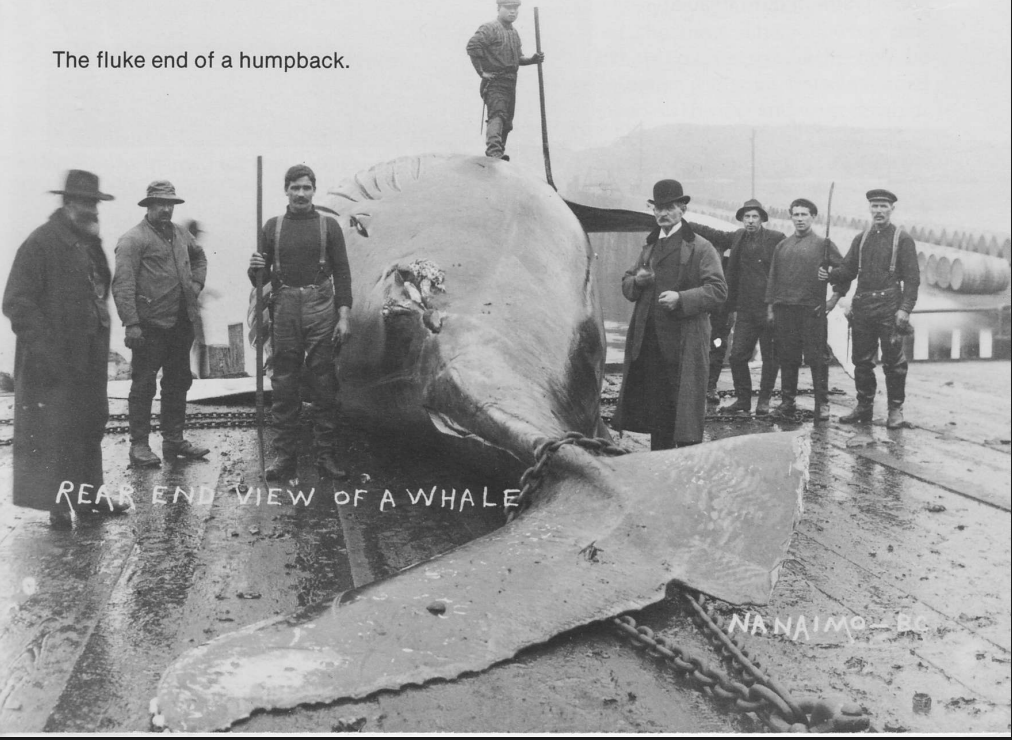

The last whaling station on Canada’s west coast closed in 1967. By that time, Humpback Whales were close to extinction and for so many years, it was a rarity to see these giants. But, slowly they started making a comeback.

We were there to document their return. We wanted to know who the whales were and make it count, not only for the wellbeing of whales, but for the ecosystem upon humans also depend.

We could never have known that this would lead to the biggest opportunity imaginable to help the world understand the importance of whales – Planet Earth III.

We worked with BBC producer Fredi Devas in 2021 and 2022, applying what we learned about individual Humpbacks to gain footage that could compel conservation. We spent a lot of time filming a new feeding strategy and . . . looking for whale poo. Sir David Attenborough would narrate this work and say the names of the Humpbacks we study. How on earth did we get here?

Witnessing the return of Humpback Whales to northeast Vancouver Island (Territory of the Kwak̕wala-speaking Peoples) is what catalyzed a group of friends to form the Marine Education and Research Society. This area is one of the most productive on the coast of British Columbia due to big tidal exchanges, cold water, and abundance of plankton.

We catalogued who the whales were, aided by data contributions from others. It soon became clear that, generally, the same Humpback Whales were returning to the same very specific areas to feed, year-after-year. Such site fidelity could allow Humpbacks to fatten up more efficiently after depleting their reserves in the warm water breeding grounds.

We formed the Canadian Pacific Humpback Collaboration (CPHC) to work with others cataloguing Humpbacks off the coast of British Columbia. Our colleagues in the CPHC witnessed the same sort of site fidelity on other parts of the coast.

For the Humpbacks who return to feed near northeast Vancouver Island, our research supports that when it comes to catching their food, their speciality is lunge-feeding on juvenile herring. With mouths open, they rush into concentrated “balls” of herring to engulf as many as possible.

Then in 2011, there was a big surprise. We saw a Humpback Whale we nicknamed “Conger” hanging vertically, almost stationary, jaws wide open at the surface. We could see right into the roof of his mouth and his wing-like pectoral fins occasionally pushed toward his jaws. We had known Conger for years but had never seen him behave like this before. What was he doing?

Conger was trap-feeding. That’s what we came to call this new feeding strategy that some Humpbacks have learned to apply under very specific conditions – when juvenile herring are not in a concentrated ball and there are birds pursuing the fish. By positioning near the herring with their mouths wide open, these Humpbacks are setting a “trap”. The fish collect near, or in, the mouth of the Humpback to escape predation by the birds (most often Common Murres and Rhinoceros Auklets). This feeding strategy uses less energy than when Humpbacks lunge-feed on greater concentrations of juvenile herring, allowing the whales to feed efficiently even when much fewer fish are present.

In 2011, we documented two Humpbacks using this completely new feeding strategy. By 2023, we know that at least 32 whales have learned to trap-feed from one another.

Trap-feeding and our knowledge of individual Humpback Whales is what drew attention from Fredi Devas for Planet Earth III.

We recognize and catalogue individual Humpbacks by the distinctive patterns on the underside of their tails (flukes) and by the markings and shape of their dorsal fins.

We also give the whales nicknames for distinctive features, which not only helps with recognizing the individuals, but also increases the potential for the public to care and undertake action for the whales. For example, the nickname “Conger” is for an eel-like marking on his fluke. This is far more compelling and easy to remember than “BCY0728” which is his catalogue designation.

Knowing who the whales are is also essential to understanding the threats they face. These include vessel strike, entanglement in fishing gear, ocean noise, and changes in prey and/or climate. But because dead whales often sink or strand in remote locations where they are never found, in many cases the cause of death is unknown and the true impacts of these threats are underestimated. This is why we study the scars of survivors. By documenting how many whales have scars from entanglement and/or collision, we can help prove how necessary it is to reduce the threats.

Other ambassador whales who were filmed for Planet Earth III include Slash (BCY0177) and her 2021 calf CAVU. The big propeller scars on Slash’s side provide stark evidence of the threat of vessel strike. Argonaut (BCY0729) was one of the Humpbacks filmed repeatedly jumping out of the water (breaching). He has scars from entanglement. Hunter (BCX1473) was one of the many whales filmed with boats nearby, including large vessels like cruise ships.

And then there were all the whales who were filmed defecating. Why was there such a focus on filming whale poo? Because that’s one of the most significant ways whales benefit human survival. Whales may feed at depth, but they always defecate at the surface. The poo serves as fertilizer leading to more plant-like plankton, and more photosynthesis in which carbon dioxide is absorbed. It’s estimated that every large whale sequesters approximately 33 tons of carbon. That’s the equivalent of around 30,000 trees.

May the stunning imagery and stories of these whales in Planet Earth III not only provide hope, but motivate meaningful, widespread action for conservation. All of us are connected to whales through our consumer and voting choices – impacting changes in climate; vessel traffic; the threat of entanglement and plastic pollution; and ocean noise.

How we treat whales will ultimately be the measure . . . of how humanity treats itself (paraphrasing Dr. Sidney Holt). Humanity needs whales.

On the production, we worked with:

- Fredi Devas, producer, whose work includes BBC’s “Seven Worlds One Planet”, Planet Earth II “Cities”, and “Frozen Planet”.

- Bertie Gregory, film-making whose work includes BBB’s “Seven Worlds One Planet”, and star of National Geographic’s “Epic Adventures with Bertie Gregory”.

- Hayes Baxley, cinematographer whose work includes Emmy award-winning “Secrets of the Whales” (Disney +).

- Tavish Campbell, dear friend and British Columbia’s cinematographer deeply dedicated to conservation on our coast.